At first glance, the Non-Condensable Gas (NCG) test for steam quality seems straightforward: cool the steam and separate the gases from the condensate. However, in practice, it is far more complex than it appears.

A Brief History of the Test

To understand the current standards, we have to look back to the 1970s. At that time, the UK Department of Health was tasked with providing assurance to Sterile Service Departments that their sterilisers were operating correctly. It’s worth remembering that 1970s-era sterilisers relied on mechanical cams and rotating drive shafts rather than modern microprocessors.

This era of innovation led to the development of the Bowie and Dick test, which remains a global standard for ensuring a steriliser can effectively remove air and achieve the necessary time, temperature, and moisture levels.

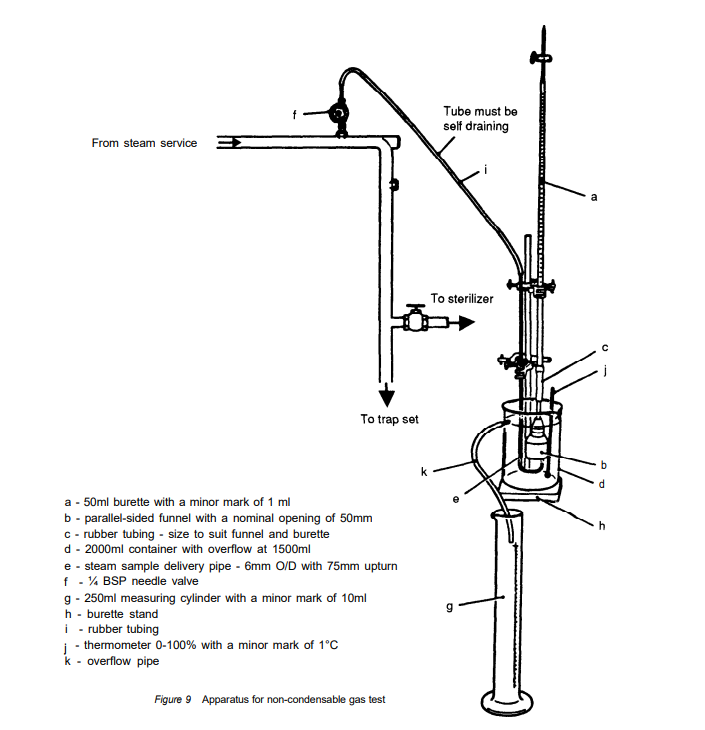

However, once these tests were introduced, some departments began experiencing unexplained failures. After thorough investigations by the Department of Health, high levels of non-condensable gases were identified as the culprit. Because this posed a potential risk to every hospital in the UK, a test rig was developed using equipment that was readily available at the time—largely borrowed from laboratory chemistry.

These early methods eventually became the standards we recognize today in HTM2010 and EN285.

And in the end the test as seen in HTM10 and onwards through HTM2010 and EN285 was put forward as the standard to use.

The Problem with the “Chemistry Class” Setup

If you look closely at a standard NCG test rig, it looks more like a high school chemistry experiment than a piece of modern pharmaceutical equipment. While the principle is sound, the pass/fail limit of 3.5% is a legacy value established decades ago.

In my experience, a 3.5% limit is achievable; failures are usually tied to boiler feed pump timing or piping issues rather than fundamental steam production problems. But there is a variable in the equipment itself that many overlook: the burette.

How Vacuum Affects Your Results

In a “standard” setup, the water level in the burette is pulled to the top using a vacuum. This is where the physics of the test becomes problematic.

According to Boyle’s Law, the volume of a gas is inversely proportional to its pressure. Any non-condensable gas entering the burette must travel through the water column. As it rises into the vacuum-pressurized space at the top, those small bubbles expand.

When we designed the SQ1P over 20 years ago, we focused on repeatability. We moved from a 50ml burette to a 25ml version (since the limit is 3.5ml, not 35ml), but we still used a vacuum to raise the water level.

With the development of the SQ1E, we changed our approach entirely. We decided that the reference pressure for the air in the burette should be atmospheric (zero). To achieve this, we placed the water outlet at the same height as the zero mark on the burette. This ensures the gas collected is not being artificially expanded by a vacuum.

The Evidence: How Much Does It Matter?

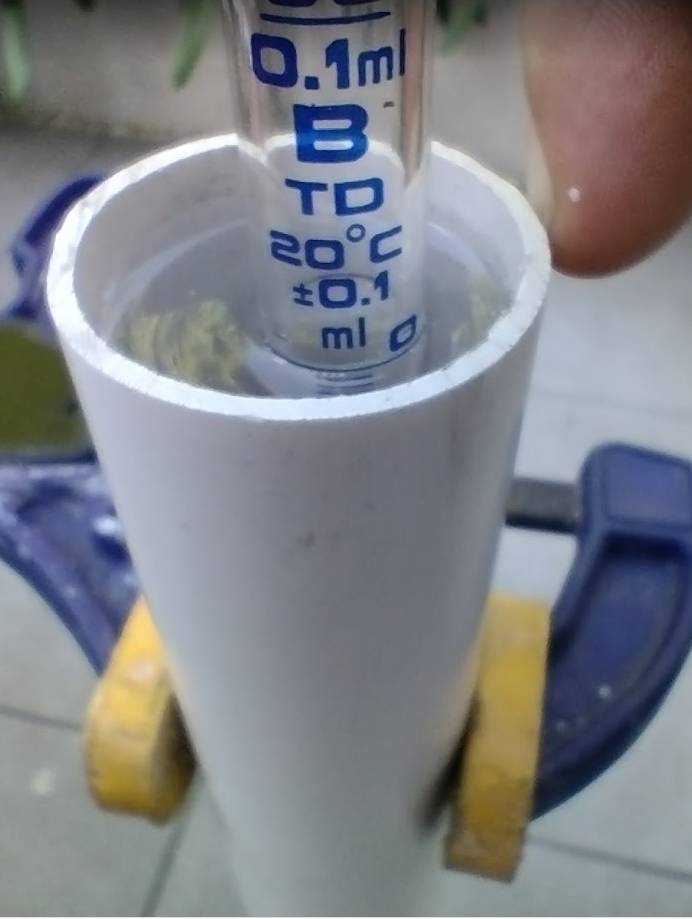

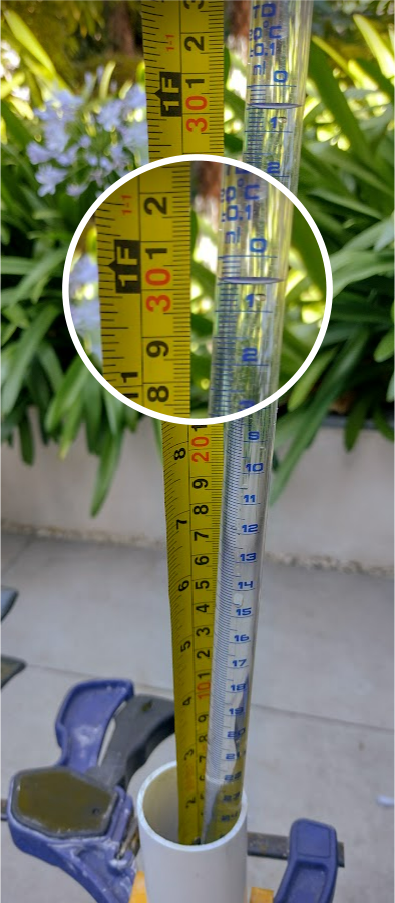

Is this effect significant, or just a minor technicality? To find out, we performed a simple test:

-

We placed a burette in a vessel of water, zeroed the level, and closed the valve.

-

We then raised the burette 300mm above the water level and inspected the volume.

The result: The air under vacuum expanded by an additional 0.4ml compared to its volume at atmospheric pressure.

In a test where the difference between a pass and a fail is measured in tenths of a milliliter, this is a massive margin. Essentially, if you use a vacuum-assisted burette, you are statistically more likely to fail the test than if you use an atmospheric-zeroed system.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, there is no “simple” fix for those using legacy equipment. I cannot recommend altering the official formula, as that would not be accepted by regulatory inspectors.

However, it is clear that the standard needs to be updated. We need a testing regime based on modern physics rather than an outdated setup that was never intended for the high-precision requirements of today’s pharmaceutical and healthcare industries.

Until the standards catch up, the best thing you can do is ensure your equipment is as accurate as possible—and understand that the “length” of your vacuum might be the only thing standing between a pass and a fail.

Don’t forget to read my blog on the issue with pitot tubes. Here.